Quinton Dixie learned a lot about the Black church by sitting in the pew as a young boy while his grandfather preached at Pilgrim Baptist Church in Fort Wayne, Ind. The Rev. John Dixie Jr. guided the church from the early 1930s until 1974, including leading the church through the turbulent 1960s.

“His shadow loomed large,” said Dixie, an associate research professor of the history of Christianity in the United States and Black Church studies. “He led protests in the 1960s … those things that shaped what the church was about.”

The legacy continued with Dixie’s father, who was an associate minister at the church. “My mother was a schoolteacher,” he says. “My love of learning came from her. Teaching about religion is the best world for me. It came from both of my parents’ interests.”

Dixie’s church was also an extension of family in broader ways. “Our church was a migration church. Congregations are collections of families, and all of them had roots in the same two counties in Alabama—Dallas and Perry Counties. Migration happens in patterns; someone goes to get a job and then sends for their family members.” The majority of the church members were working class families with jobs at the local factories, steel mills, and International Harvester in Fort Wayne.

The Value of Churches in Public Policy

Dixie’s current academic and research interests reflect his cultural legacy. He specializes in American religious history and has written on a wide range of topics—from the African American civil rights movement to the history of Black Baptists in the United States.

He has a bachelor’s degree in urban policy from James Madison College at Michigan State University. “I fantasized about life in city government,” Dixie said. “I’m still interested in public policy and how churches can encourage change through public policy.”

More specifically, Dixie is interested in the church being intentional and proactive in changing long-term policy rather than be reactionary after something has happened. He contrasts that with how far in advance government and businesses plan. For instance, “I recall when the RCA Dome was the big football arena for the Indianapolis Colts, but officials were already planning for the next arena,” he said. “Stadiums like the RCA Dome last around 15 to 20 years, and as it was being completed civic groups were already thinking about there the next one (Lucas Oil Stadium) would go and what it would take to make it happen.”

By contrast, Dixie notes that churches rarely have this habit and practice of planning and advocating for the future. “African American churches generally react in moments of crisis through protest,” he said. “I want to help congregations and communities to think proactively about how to generate long-term change that comes through policy formation. It doesn’t make headlines like protest, but it is just as important, if not more.”

For Dixie, his fight for civil rights was the anti-apartheid movement. He remembers that Baptist minister and longtime General Motors board member Leon Sullivan developed the Sullivan Principles for doing business in South Africa. American companies who agreed to the Sullivan Principles pledged to do business in South Africa only with companies who did not discriminate on premises (requiring integrated restrooms, cafeterias, etc.) or employment (requiring equal and fair practices and pay); who invested in Black job training and increasing the number of nonwhites in management roles; and who improved the quality of life for Blacks and nonwhites outside the work environment (for example, housing, schools, health facilities and access, etc.).

Through Sullivan’s work, over 125 corporations joined General Motors in adopting the Sullivan Principles. “It was a way for the American business community to have established guidelines for how to do business in a country that had customs and laws that violated human rights as established in the U.S.,” Dixie said. “There’s an ethical way of doing business and there’s an unethical one. Black churches have a long history of engagement with public policy to rekindle those conversations today. You saw them in the chants during the George Floyd protests, for instance. We need to talk about policing and gun control.”

The Value of History for the Present

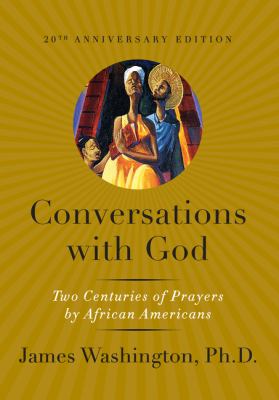

Dixie earned his master’s degree and Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York and developed an interest in documentary editing early in his career. He worked on two projects with James M. Washington, the noted historian, minister, and educator, while still a graduate student: I Have a Dream, a collection of Martin Luther King Jr.’s writings and speeches for young adult readers; and Conversations with God, an edited volume of African American prayers over two centuries, from the late eighteenth through the late twentieth centuries. He received a certificate from the Institute for the Editing of Historical Documents and for 15 years was on the editorial team of the Howard Thurman Papers Project.

Dixie earned his master’s degree and Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York and developed an interest in documentary editing early in his career. He worked on two projects with James M. Washington, the noted historian, minister, and educator, while still a graduate student: I Have a Dream, a collection of Martin Luther King Jr.’s writings and speeches for young adult readers; and Conversations with God, an edited volume of African American prayers over two centuries, from the late eighteenth through the late twentieth centuries. He received a certificate from the Institute for the Editing of Historical Documents and for 15 years was on the editorial team of the Howard Thurman Papers Project.

“When I worked with the Howard Thurman material, I went through his sermons, essays, and newspaper articles,” Dixie said. “They give you the story of that individual’s career. I even looked at what classes he took, who gave him recommendations.”

Dixie finds that knowledge important to share with his students. “It gave me access to primary material that students won’t have. I can share my perspective as someone who sat and read through sermons, letters. From that I can cull out things that are in the books and create a portrait of an era.”

When Dixie is not talking about religion and history, he enjoys running. He was a longtime track coach in Indiana before moving to Duke Divinity School. “I love track and field!” he said. “I ran track in high school myself. I became involved in coaching with my own children when my kids attended the same school I attended.”

He sees the sport as a metaphor of Christianity. “It’s a team sport, but every individual is also competing with their own personal history and ability. You can lose a race and have a good day because you ran a good race. Christianity is about self-improvement and development—I’m not where I need to be, but I’m better than I was.”