A core value at Duke Divinity School is the call and commitment to welcome voices into the conversation and community here. This includes people who participate in the life and mission of the school, the texts studied and taught, and the vision for diversity in ministry partners and contexts. Three new faculty who joined the school this fall exemplify these commitments: Daniel Castelo, William Kellon Quick Professor of Theology and Methodist Studies; Polly Ha, associate professor of the history of Christianity; and Ronald K. Rittgers, Duke Divinity School Chair in Lutheran Studies and Professor of the History of Christianity.

From excavating early modern texts in order to hear the voices obscured by time or culture to embracing the insights of Latinx theologies and pastoral experiences, Castelo, Ha, and Rittgers add rich perspectives to the teaching and scholarship at Duke.

“Part of participating in a vision of the new Pentecost here at Duke Divinity School includes welcoming new voices into our community,” said Edgardo Colón-Emeric, dean of Duke Divinity School and the Irene and William McCutchen Associate Professor of Reconciliation and Theology and director of the Center for Reconciliation. “These three new faculty bring research expertise, perspectives on the church, and a passion for theological education that embraces interdisciplinary dialogue. We welcome their gifts to listen to and learn from the church throughout history and around the world.”

Daniel Castelo

William Kellon Quick Professor of Theology and Methodist Studies

Castelo is no stranger to Duke or Durham, having earned his Ph.D. here while also teaching intensive Wesleyan theology courses in Mexico, Honduras, and Brazil. After completing his doctoral work, he taught at a seminary in Mexico for three years before moving to Seattle Pacific University, where he has taught dogmatic and constructive theology for 14 years. He has published extensively on the topics of divine attribution, the doctrine of God, Christian pneumatology, and more.

“I felt called to come not just to a divinity school per se, but to this divinity school,” Castelo said. “I had conversations with the leadership of Duke Divinity before I came, and I was sold on the vision they were sharing with me. This vision included a more robust Latinx presence and outreach as well as a more pan-Methodist outlook. Both themes matter quite a bit to me. With this vision, I came to believe that Duke Divinity would be an ideal next chapter in my vocational life, allowing me new and different opportunities for teaching, scholarship, and ministry overall.”

I am excited for what I sense to be increased interdisciplinarity in the theological disciplines and even between those disciplines and other disciplines in the academy. In relation to the former, I sense the theological academy being less and less siloed as different kinds of media (such as hymns, sermons, and biblical commentaries) are being recognized for their theological integrity and worth. As to the latter, I continue to be encouraged by efforts to connect theology with the physical and behavioral sciences by various people, agencies, and institutions. I have to say that in my short time here, I sense this increasingly at Duke in terms of the Divinity School and its connection to other parts of the university. These developments are all very exciting.

I am not that keen on numbers as indicators of the church’s health. I am encouraged by the students I have, the questions they ask, and the love for people and for justice I sense in them. Yes, these are polarizing times, particularly in our politics. But the church has real opportunities at this moment to step in and show “a more excellent way.” In the midst of varying kinds of destabilizations of arrangements and power structures, the church can find itself anew. I see vast potential for the church in this country to be renewed by the power of the Holy Spirit at this time when we are reckoning with our needs, faults, history, and limits.

Polly Ha

Associate Professor of the History of Christianity

Ha, who joins Duke Divinity from the University of East Anglia, specializes in reception studies of the Reformation, ecclesiastical thought, historical method, political theology, and the wider impact of reformation on men and women across the social order. Among her other publications, she is chief editor of The Puritans on Independence (Oxford University Press, 2017) and Reformed Government (Oxford University Press, 2021), which include debates over conciliarism, historical contingency, and institutional mutability in response to Richard Hooker’s Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity.

Ha is currently working on a new archive of manuscripts that includes some of the earliest debates in English over concepts that we are still debating today: Independence, freedom, consent, conscience.

“Finding these manuscripts felt like playing the part of Indiana Jones—a sort of raider of lost manuscripts! A number of factors conspired to conceal these papers for nearly four centuries. Walter Travers never intended his manuscripts to be discovered. As a leading puritan critic of the Church of England, he was considered an enemy of the state. His papers were full of subversive content. And he even encrypted some of his writing in code using Greek characters to write in English, Latin, and French. (Not to mention his atrocious handwriting.)

“But thankfully he left clues. The first was a series of notes one of his students took from his lectures when he was provost of Trinity College Dublin. Next were an archivist’s annotations in a library catalogue in Dublin suggesting a handful of manuscripts belonged to Travers. But that was only the tip of the iceberg. I was able to reconstruct more of Travers’s hidden archive by using former shelf-marks on the spine of the manuscript volumes and by deciphering his papers at Trinity. These included over 400 pages documenting some of the earliest debates over the concept of freedom as independence in the English-speaking world. How do we reconcile personal freedom with our wider obligations to civil society? How do we understand the relationship between political and religious freedom and the expansion of social justice? What the Travers archive reveals is the interwoven nature of the entire tapestry. Early modern debates rarely considered equality or any one aspect of freedom in isolation from others. They found the space to think broadly and deeply, which meant that they were attuned to how all of these individual parts related to each other and affected the whole.”

My growing passion for history dovetailed with my personal journey of faith and knowledge of Christ. I was full of questions. Where and how do I worship? What is the church? Not having been brought up in any church, I didn’t know where to begin.

Thankfully, I was in good company. Protestant Reformers were asking the same questions following their break with the Roman Catholic Church. What constituted the true church? Should they conform to the religious status quo? At what point should they cut loose and venture into the unknown? I’ve been studying those questions ever since. The longer I study them, the more my appreciation grows for the Reformers’ simultaneous realism and vision. They were deeply committed to checking the abuses of power. But that didn’t stop them from pursuing their wider aspirations and ecclesiastical ideals.

History liberates us from being imprisoned in the present. It broadens our perspective. It challenges our assumptions. But history has a special significance for students of divinity. Christianity is of course rooted in history. It is inescapably historical. Our present and future will only be impoverished, and scarcely understood, without it.

Ronald K. Rittgers

Duke Divinity School Chair in Lutheran Studies and Professor of the History of Christianity

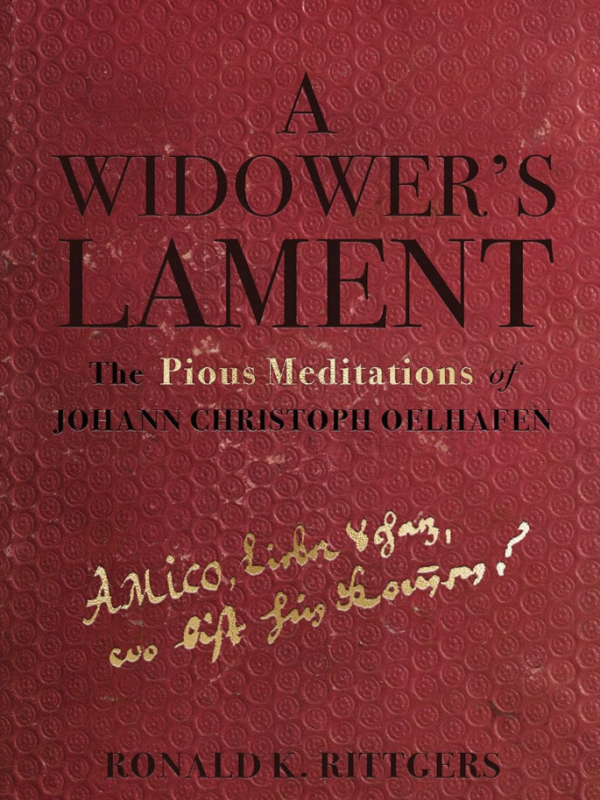

Rittgers, a past president of the American Society of Church History, is interested in the religious, intellectual, social, and cultural history of medieval and early modern/Reformation Europe, focusing especially on the history of theology and devotion. His most recent book is A Widower’s Lament: The Pious Meditations of Johann Christoph Oelhafen (Fortress, 2021).

Rittgers discovered the Oelhafen manuscript in the German national archives in Nuremberg while doing other research on how lay people experienced suffering during the Reformation period. This firsthand lay record of the experience of grief, written in 1619, had been seen by very few people and never translated.

“Oelhafen’s year-long lament is, on the one hand, time-bound, existing as an artifact of the distant past and its unique culture, but, on the other hand, it is remarkably relevant to contemporary experiences of grief in western Christian contexts,” Rittgers says.

“Oelhafen looks for consolation through Scripture, song, verse, sacraments, friends, and, ultimately, our gracious Lord. He is honest about the deep pain that the loss of his wife of 18 years has caused him, wondering why God has allowed it—his meditations are ‘raw,’ in this sense. He may connect his loss more directly to the divine will and his own sin than some modern Christians permit, but others will find these themes to be entirely plausible. Most important, he turns to lament to deal with his grief and suffering—he pours out his broken heart to God looking to God for comfort and help. That’s good in any century.”

Why study history? Because Christianity is a historical religion and we have much to learn (and to avoid) from the past. Studying the past also works against American a-historicism, which afflicts many churches as well as other institutions.

I am grateful to return to a context where teaching theology—broadly construed—is the main project. I am also grateful to be in a context that has a real chance to serve, shape, and even reform American Christianity (and beyond) in very challenging days for the church. Because of its abiding commitment to the church, and because of its centrist theological culture and identity, Duke Divinity is uniquely situated among university-based divinity schools for this important work.