When Xi Lian, professor of world Christianity at Duke Divinity School and a renowned scholar of China’s modern encounter with Christianity, first heard the story of Chinese dissident Lin Zhao, he was enthralled. “She was the lone dissident in the 1960s who held out in this seemingly hopeless resistance against Mao’s Communism, at a time when intellectuals—and everybody, actually—had been silenced,” he said.

Lin Zhao was known in China for the protest writings she made in prison using her own blood and for the five-cent bullet fee that authorities forced her family to pay after her execution. But she was little known in the United States, and her life and the Christian faith that drove her was a compelling subject for Lian, who spent seven years researching and writing the first authoritative biography of her, Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao’s China (2018). The New York Review of Books called it “one of the most important books on the Communist-era rights movement to be published in recent years.”

A Spellbinding Story

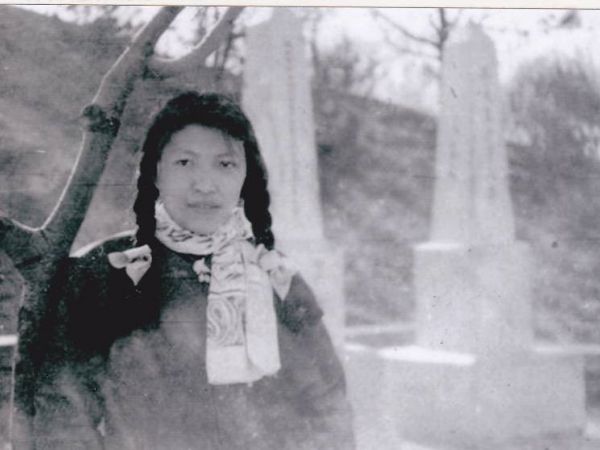

Lian first saw Lin Zhao’s writings in person at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. It was a special moment for the scholar. “I came face-to-face with her writing, and I was held spellbound by her words—just looking at her handwriting,” he said. A year later, in the spring of 2013 when Lian was back in China to conduct research, he visited her burial place. “I went to her tomb and sat there, taking in that loneliness there,” he said. “I felt a sense of responsibility and privilege to be able to tell her story.”

Lian was especially interested in finding out what gave Lin Zhao her moral autonomy in opposition to state orthodoxy and her hope in the midst of a seemingly futile and suicidal opposition.

“I came face-to-face with her writing, and I was held spellbound by her words—just looking at her handwriting."

As a teenager in 1947, two years before the Communist Revolution, Lin Zhao started attending the Laura Haygood Memorial School for Girls, a Southern Methodist mission school in Suzhou.

There, she took part in a liberal education with a Christian influence that together helped form in her the concept of a kind of modern Christian womanhood. Lin Zhao converted to Christianity and was baptized at the school. Shortly after, she secretly became a member of the Communist Party as well, at the age of 16—a risky proposition under the existing Nationalist regime, but one that promised a “new China” that appealed to the young woman with modern ideals.

Ultimately punished for her views during Mao’s 1957 anti-rightist campaign, Lin Zhao became disillusioned with the Communist Revolution, came back to the church, and embarked on her dissent. She was arrested but refused to be silent, pricking her finger to write protest poems and letters in her own blood. Her original 20-year prison sentence was secretly changed to the death penalty, and she was executed on April 29, 1968.

A Musical Tribute

Lian became engaged in the story of Lin Zhao after seeing a film directed by Hu Jie, “Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul.” So the idea of honoring Lin Zhao in another medium seemed natural. Having devoted so much time and scholarship to the story of this remarkable young woman, Lian wanted to find some public way to remember and honor Lin Zhao. “The idea for a musical piece came to me because, sadly, there has not been any public remembrance of Lin Zhao,” he said. A friend of his in China, Lu Pei, was a composer and had wanted for some time to compose a piece to honor Lin Zhao.

“Could Duke Divinity School be the catalyst for this project?” Lian wondered. He approached Jeremy Begbie, Thomas A. Langford Distinguished Professor of Theology and director of Duke Initiatives in Theology and the Arts (DITA), about the idea of commissioning Lu for a work honoring Lin Zhao.

DITA’s goal is to promote engagement between Christian theology and the arts and explore how the arts are modes of theological expression themselves. The project was a great fit. Begbie was on board, and the collaboration that would cross disciplines and continents was born.

Listen to Frank Stasio interview Lian and Begbie on WUNC’s “The State of Things.”

Begbie had a close relationship with a number of performers from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, musicians of faith who he thought would be interested in participating. DITA commissioned Lu to compose Elegy, which would premiere at Duke Divinity School in Spring 2019 with Begbie on piano, along with three Boston Symphony Orchestra players: John Ferrillo on oboe, Elizabeth Ostling on flute, and Bill Hudgins on clarinet.

Lu, a composer with a modernist bent who refers to classic Western works in compositions that are still distinctly Chinese, wrote a piece that evokes the harshness of Lin Zhao’s imprisonment as well as the divine mercy and redemption that sustained her. “The part of Lin Zhao’s story that was particularly inspiring for me was her steadfast faith,” Lu said. “She stood strong in her struggle against the forces of evil and was unbending in her resistance. That would not have been possible without her faith. My music attempts to reveal Lin Zhao’s mental world, and to capture her faith and her inner surges—her prayers and her hopes, her love for humanity and for God. Even though there was much evil and darkness in the world, love still remained.”

The piece premiered March 29 at Duke Divinity School’s Goodson Chapel, opening an evening dedicated to honoring the legacies of martyrs, “Performing Faithfully: Music & Martyrdom.”

“If Lin Zhao were with us today, I think she would say that God has been faithful to her. She had fought a good fight, and had kept her faith, and God sees that it was not in vain,” said Lian.

The premiere of “Elegy” and the “Performing Faithfully: Music & Martyrdom” event were made possible with the generous support from the Office of the Vice Provost for the Arts at Duke University through a Collaboration Development Grant, and was co-sponsored by the Duke Department of Music, the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, and the Asian Pacific Studies Institute.