Prison Studies at Duke Divinity

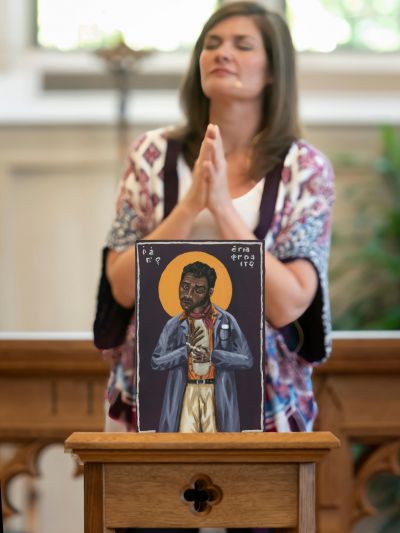

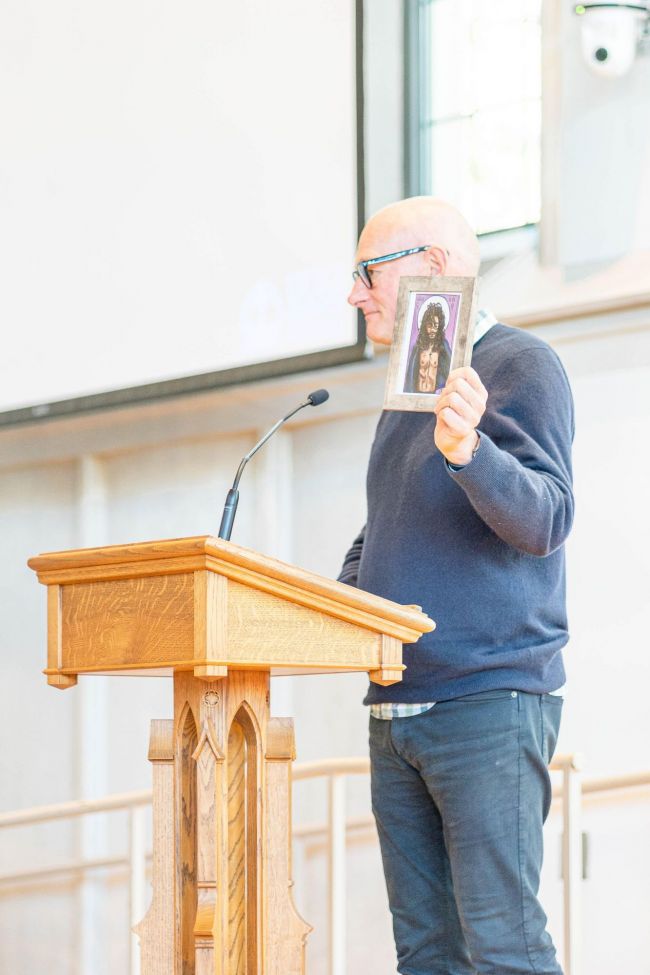

Duke Divinity School's engagement in prison studies includes courses taught to both Divinity students and incarcerated students, a Certificate in Prison Studies offered to Divinity students, a certificate offered to incarcerated students, the Prison Justice Action Committee student group, and events hosted throughout the year.